Can an antibiotic help a fungal eye infection? It sounds backward, but it’s a fair question clinicians face in the clinic when a corneal ulcer looks fungal and the stakes are high. Here’s the short answer: besifloxacin does not kill fungi, but there may be narrow, indirect reasons to consider it alongside antifungals in very specific scenarios. Expect nuance, clear limits, and practical guidance-not a magic bullet.

TL;DR

- Besifloxacin is an antibacterial fluoroquinolone. It has no proven antifungal activity and is not a substitute for natamycin, amphotericin B, or voriconazole.

- Possible indirect benefits: cover bacterial coinfection, reduce bacterial bioburden in mixed ulcers, and protect against secondary infection during antifungal therapy.

- Evidence is limited to rationale and practice patterns; there are no randomized trials showing improved outcomes in fungal keratitis with besifloxacin adjuncts.

- Standard of care in 2025: natamycin 5% first-line for filamentous fungi; amphotericin B 0.15% for yeasts; voriconazole is situational. Start antifungals promptly.

- Use adjunct antibacterial coverage only with clear reasoning (coinfection risk, severe ulcer while awaiting cultures). Avoid delaying or diluting antifungal therapy.

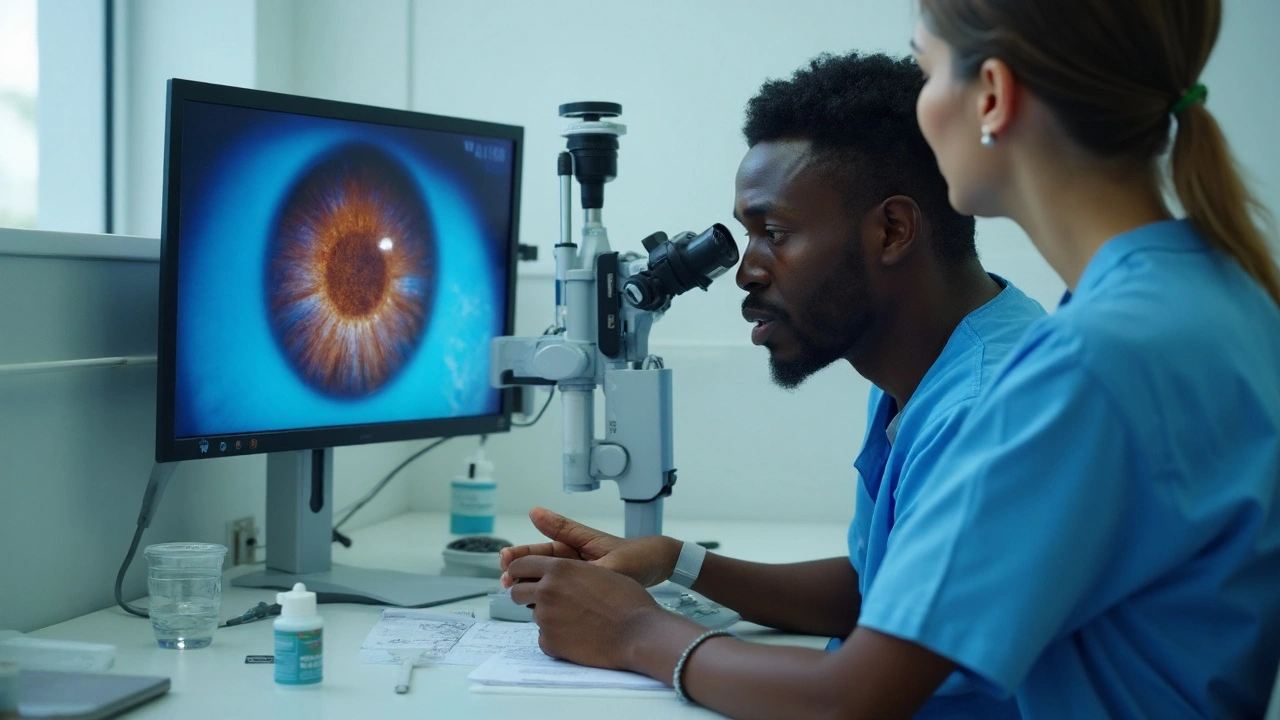

What besifloxacin can-and can’t-do in fungal ocular infections

Let’s set the record straight. besifloxacin is a topical fluoroquinolone antibiotic approved for bacterial conjunctivitis. It targets bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. Fungi don’t respond to this mechanism at achievable ocular concentrations. In other words, if your patient has fungal keratitis, besifloxacin won’t treat the fungus.

Regulatory status backs this up. The U.S. prescribing information for besifloxacin (ophthalmic suspension 0.6%) indicates use for bacterial conjunctivitis only. It does not claim antifungal activity. The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Preferred Practice Pattern (PPP) on Fungal Keratitis (most recently updated pre-2025) recommends natamycin 5% as first-line therapy for filamentous disease (especially Fusarium), amphotericin B for yeasts, and considers voriconazole in select situations. None of these guidelines list fluoroquinolones as antifungal treatments.

So where does the discussion even come from? Two places:

- Mixed infections happen. Corneal ulcers may present with fungal features but also harbor bacteria. Clinicians sometimes add antibacterial coverage at the start, then narrow therapy once microscopy/culture or in vivo confocal microscopy clarifies the cause. The goal is to avoid missing a concurrent bacterial pathogen during the first 24-48 hours.

- Secondary bacterial infection is a risk. A compromised epithelium is a doorway for bacteria. While antifungals do the heavy lifting, an antibacterial can reduce the chance of a secondary bacterial hit that worsens the ulcer or blunts recovery.

What makes besifloxacin a candidate for that antibacterial role? A few practical features:

- Potent Gram-positive coverage, including MRSA. In vitro, besifloxacin shows strong activity against staphylococci and streptococci-common culprits in bacterial keratitis. Reports from ophthalmic susceptibility programs (late 2010s-early 2020s) consistently place its MICs favorably versus other topical fluoroquinolones.

- Formulation that sticks around. The DuraSite vehicle increases corneal contact time, which supports high ocular surface exposure. Pharmacokinetic studies in animal models and human tear film show sustained levels compared with standard solutions.

- Low systemic exposure. Topical-only use means minimal systemic absorption, which is good for stewardship and safety.

Now the limits:

- No antifungal kill. There’s no credible evidence that besifloxacin inhibits Fusarium, Aspergillus, or Candida at clinical doses. Fluoroquinolones target bacterial enzymes; fungal topoisomerases are not meaningfully hit in vivo.

- No clinical trials for fungal keratitis adjunct use. We lack randomized data showing that adding besifloxacin to natamycin/amphotericin/voriconazole improves healing time, perforation risk, or vision versus antifungals alone.

- Potential to distract from the main job. If an antibacterial gives a false sense of security and delays adequate antifungal loading or debridement, outcomes can suffer.

What does high-quality evidence say about managing fungal keratitis? Key anchors:

- MUTT I (Ophthalmology, 2013): In filamentous keratitis, natamycin outperformed topical voriconazole, especially in Fusarium. This trial reset many treatment habits toward natamycin-first.

- AAO PPP Fungal Keratitis (2023 update cited in 2025): Start antifungals promptly based on clinical suspicion; confirm with smear/culture if possible; consider debridement; escalate to intrastromal/intracameral therapy or keratoplasty if needed.

- Cochrane Review (latest update pre-2025): Supports natamycin’s advantage in filamentous disease; evidence for combination regimens is still evolving.

Bottom line for this section: besifloxacin is not an antifungal. Its potential relevance in fungal keratitis is limited to antibacterial coverage when there is a reasonable suspicion of bacteria in the mix or high risk of secondary infection-never as a stand-alone treatment for a fungal ulcer.

| Property | Why it matters in fungal ulcers | Evidence strength (2025) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoroquinolone mechanism (anti-bacterial) | No direct antifungal activity | High (mechanistic consensus) | Targets bacterial gyrase/topoisomerase IV; fungi not affected at clinical levels |

| Broad Gram-positive & Gram-negative coverage | Useful if bacterial coinfection or secondary infection risk | Moderate (in vitro + clinical experience) | Active against staphylococci including MRSA in many regions |

| DuraSite vehicle (longer contact time) | Higher, more sustained ocular surface exposure | Moderate (PK studies) | May support bioburden control while antifungals act |

| Direct antifungal effect | None | High (negative evidence) | Not a replacement for natamycin, amphotericin B, or voriconazole |

| Impact on clinical outcomes in fungal keratitis | Unproven | Low (no RCTs) | Adjunct role remains a practice decision, not guideline-backed |

Where besifloxacin might fit: adjunct roles, decision checks, and real-world scenarios

When would a careful clinician even reach for besifloxacin in a likely fungal ulcer? Three situations come up:

- At presentation, etiology unclear. The ulcer looks filamentous, but Gram stain/KOH prep/culture are pending, and there’s marked suppuration or hypopyon. You start natamycin right away and consider a topical antibacterial to avoid missing a bacterial component in the first 24-48 hours. Once diagnostics clarify the picture, you de-escalate.

- Clear fungal keratitis, but coinfection risk is high. Examples: contact lens misuse with poor hygiene, agricultural trauma with contaminated matter, or prior topical steroid use. Here, adjunct antibacterial coverage can be reasonable for a short window.

- Worsening course despite appropriate antifungals. If there’s new purulence, increasing pain, or changing infiltrate edges suggestive of bacteria, temporary antibacterial coverage while re-culturing makes sense.

Why besifloxacin versus other topical antibacterials like moxifloxacin or gatifloxacin? It’s a trade-off:

- Pros: Potent Gram-positive activity (including MRSA in many locales), sticky formulation for increased surface time, minimal systemic exposure.

- Cons: Cost and availability can be limiting in some regions; no proven superiority over fourth-generation fluoroquinolones in fungal scenarios; not on label for keratitis of any type.

Here’s a simple, practical decision check you can run quickly at the slit lamp:

- Does the ulcer scream “fungal”? Feathery margins, satellite lesions, dry texture, raised necrotic slough, history of vegetative trauma, or slow response to antibiotics. If yes, start antifungal therapy immediately.

- Any red flags for mixed infection? Dense suppuration, mucopurulent discharge, rapid central thinning, significant pain out of proportion, prior contact lens wear in poor hygiene contexts. If yes, consider adding a topical antibacterial while you wait for microscopy/cultures.

- Reassess in 24-48 hours. If smears/cultures confirm fungus alone and the course is steady or improving, taper off the antibacterial and keep the antifungal plan. If bacteria are found (or clinical course points that way), continue targeted antibacterial therapy alongside antifungals.

- Don’t let adjuncts slow the main therapy. Debridement when needed, adequate antifungal frequency, and close follow-up matter more than the choice of adjunct antibacterial.

Stewardship and safety tips that help:

- Keep the focus on antifungals. Natamycin 5% leads for filamentous disease. Amphotericin B 0.15% is preferred for yeasts. Voriconazole has a role but was inferior to natamycin in Fusarium in MUTT I.

- Limit the antibacterial window. If you add besifloxacin, reassess quickly. Stop it if cultures and clinical course say “fungus only.”

- Avoid topical corticosteroids early. Steroids can worsen fungal keratitis or mask progression. If you consider them later, it should be cautious, after clear improvement on antifungals and with culture guidance.

- Document everything. Entry size/depth, epithelial defect, stromal thinning, and photos. This keeps the team honest about true change over time.

Evidence snapshot you can cite in conversation:

- FDA labeling: besifloxacin is indicated for bacterial conjunctivitis; no antifungal activity is claimed.

- AAO PPP Fungal Keratitis (2023): natamycin-first for filamentous; amphotericin B for yeasts; voriconazole is nuanced; adjunct antibacterials may be considered when bacterial involvement is suspected.

- MUTT I (Ophthalmology, 2013): natamycin outperformed topical voriconazole in filamentous infections, especially Fusarium.

- Clinical reviews up to 2025 (Eye, Clinical Microbiology Reviews): No clinical evidence supports fluoroquinolones as antifungals; their role is antibacterial coverage in select cases.

Common pitfalls to avoid:

- Using an antibacterial alone while “watching” a likely fungal ulcer. This risks rapid progression and perforation.

- Assuming a cleaner-looking ulcer equals control. Fungal load can rise even if surface debris decreases.

- Not re-culturing a worsening case. If the ulcer changes character, sample again, including for bacteria and Acanthamoeba.

| Adjunct use case | Rationale | What to watch | Stop/Continue cue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial presentation, etiology unclear | Protect against missed bacteria while starting antifungals | Clinical improvement within 48h; culture results | Stop adjunct if fungus-only confirmed and improving |

| High risk of coinfection | Contact lens misuse, vegetative trauma, heavy discharge | Signs of bacterial activity (purulence, edema pattern) | Continue if bacteria cultured; otherwise taper |

| Worsening on antifungals alone | Possible new bacterial superinfection | Purulence rise, new infiltrate edge, pain spike | Adjust based on new cultures and response |

Evidence, gaps, mini‑FAQ, and practical checklists

What we know in 2025: Standard antifungals determine outcomes in fungal keratitis. Diagnostic speed, antifungal access, and close follow-up matter most. Adjunct antibacterials, including besifloxacin, are optional tools for narrow scenarios-not core therapy. We still need better trials to answer whether adjunct antibacterials improve vision or prevent perforation when fungi lead the pathology.

Research gaps worth closing:

- Prospective adjunct trials. Randomized, pragmatic studies comparing “antifungal alone” vs “antifungal + antibacterial” in high-risk mixed-picture ulcers could settle this.

- Microbiome and biofilm work. How antifungals and antibacterials interact on the ocular surface biofilm is under-studied.

- Region-specific resistance trends. Local data on staph/strep susceptibility to besifloxacin and its peers will improve empiric picks.

Quick clinician checklist (use as a mental run-through):

- Do I have strong clinical signs of fungus? Start antifungals now.

- Have I scraped/sent for microscopy and culture (fungal and bacterial)? If not, do it.

- Is there a credible bacterial angle (discharge, pain spike, risk history)? Consider short-course adjunct antibacterial.

- Did I set a 24-48 h reassessment? Document size, depth, thinning; photograph.

- Am I avoiding early steroids? Revisit later only if controlled and indicated.

- Do I have a plan for escalation (intrastromal/intracameral therapy, keratoplasty) if the ulcer worsens?

Mini‑FAQ

- Does besifloxacin kill fungi?

No. Fluoroquinolones don’t have meaningful activity against Fusarium, Aspergillus, or Candida at clinical doses. - Is besifloxacin recommended by guidelines for fungal keratitis?

No. AAO PPP focuses on natamycin, amphotericin B, and voriconazole. Antibacterials are considered only when bacterial involvement is suspected. - Could besifloxacin help by reducing inflammation?

Lab work suggests some fluoroquinolones may modulate inflammatory mediators, but there’s no clinical evidence this changes fungal keratitis outcomes. - Any safety concerns when combining with antifungals?

Clinically, combining topical antibacterials with antifungals is common at presentation. Watch for surface toxicity and reassess frequently. The bigger risk is delaying or under-dosing antifungals. - What about moxifloxacin or gatifloxacin instead?

They’re reasonable alternatives for antibacterial coverage. Choice often follows local susceptibility data, availability, cost, and clinician comfort. - Should patients start besifloxacin on their own for a suspected fungal infection?

No. Suspected fungal keratitis is an emergency for an eye‑care specialist. Self‑treating with antibiotics can delay proper antifungal therapy and worsen outcomes.

Examples that mirror clinic reality:

- Case A: Farm worker with vegetative trauma, feathery central infiltrate, satellite lesions. KOH smear shows hyphae within an hour. You start natamycin and do not add an antibacterial-no purulence, clean history. The ulcer improves by day 2. No need for besifloxacin.

- Case B: Contact lens wearer, poor lens hygiene, central ulcer with mixed features, mucopurulent discharge. Smear pending. You start natamycin and add an antibacterial while awaiting results. Culture later shows Fusarium plus Staph aureus. You continue both with targeted plans. Here, besifloxacin is a reasonable antibacterial choice.

- Case C: Candida keratitis after penetrating keratoplasty. You start amphotericin B. On day 3, new purulence appears; you add antibacterial coverage, re-culture, and adjust once bacteria are identified. Besifloxacin would be one option to cover Gram-positives pending results.

For completeness, here are the core antifungal anchors you’ll discuss with any team member on call:

- Natamycin 5%: first-line for filamentous fungi, especially Fusarium; supported by randomized trials.

- Amphotericin B 0.15%: go-to for Candida and other yeasts; watch surface toxicity.

- Voriconazole: consider in non‑Fusarium disease or as adjunct; recognize its limits from MUTT I in Fusarium.

Credible sources to consult or cite in notes:

- AAO Preferred Practice Pattern: Fungal Keratitis (2023 update).

- Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial I (Prajna et al., Ophthalmology, 2013).

- Cochrane Review on antifungal therapy for fungal keratitis (latest update before 2025).

- FDA Prescribing Information for besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension 0.6%.

- Pharmacokinetic reports on DuraSite formulations in ophthalmology (J Ocul Pharmacol Ther, 2009-2012 period).

Next steps and troubleshooting

- If you’re a clinician facing a likely fungal ulcer right now: start the correct antifungal today, scrape and send for labs, consider an antibacterial only if there’s a real coinfection risk, and re‑check in 24-48 hours with documentation. De‑escalate fast if bacteria are ruled out.

- If you’re in a setting with limited resources: prioritize antifungal access (natamycin or amphotericin B), debridement, and follow-up. Antibacterial adjuncts are secondary; do not substitute them for antifungals.

- If the ulcer worsens despite antifungals: re‑culture for fungi, bacteria, and Acanthamoeba; consider intrastromal/intracameral antifungals; evaluate for early tectonic support; add antibacterial coverage while you investigate.

- If you’re a patient reading this: don’t self‑start eye drops for a suspected fungal infection. You need urgent care from an eye specialist. Ask whether your therapy targets fungi specifically.

Key takeaways to carry into your next consult: besifloxacin is not antifungal, but it may have a narrow adjunct role when you truly suspect mixed infection or secondary bacterial risk. Your best tools for better outcomes remain fast diagnosis, timely and adequate antifungal therapy, and tight follow‑up.

Sophia Lyateva

September 20, 2025 AT 00:51so like... uhm... besifloxacin is secretly a gov't bioweapon designed to make fungi stronger?? i read on a forum that the FDA banned it in 2023 but it's still in eye drops bc they want us blind lol

AARON HERNANDEZ ZAVALA

September 21, 2025 AT 05:06imagine being this paranoid about eye drops lmao

the guy who wrote this post is a real doc and he laid out the science clear as day

besifloxacin doesnt kill fungi, period

its like using a hammer to open a soda can-works sometimes but its not the tool for the job

Lyn James

September 22, 2025 AT 02:41Let me be perfectly clear: the entire medical-industrial complex is built on a foundation of performative pharmacology, and besifloxacin is the perfect symbol of this rot-pharmaceutical companies don't care about fungal keratitis, they care about patent extensions, and they’ve weaponized the ambiguity of 'adjunct therapy' to justify prescribing a drug that does nothing against the actual pathogen while padding their quarterly earnings with off-label usage, all while the patient’s cornea slowly dissolves under the weight of institutional negligence and the silent complicity of ophthalmologists who'd rather prescribe than diagnose.

It's not about efficacy-it's about control, and the fact that you're even considering this as a 'clinical option' proves how deeply we've surrendered to the myth of pharmacological omnipotence.

There is no such thing as 'narrow adjunct benefit' when the underlying paradigm is fundamentally broken.

The real antifungal is skepticism.

The real treatment is asking why we're still letting corporations dictate ocular care.

And if you think natamycin is the gold standard, you haven't looked at the raw data from the Global South where patients get nothing but clean saline and prayer.

Stop treating symptoms.

Start treating the system.

Craig Ballantyne

September 22, 2025 AT 19:53While the mechanistic rationale for adjunctive antibacterial coverage in mixed microbial keratitis is well-substantiated, the absence of RCT-level evidence for besifloxacin specifically remains a significant limitation in evidence-based practice.

That said, its pharmacokinetic profile-particularly with the DuraSite formulation-offers a plausible theoretical advantage in sustained corneal bioavailability over other fluoroquinolones, which may justify its empirical use in high-risk settings pending diagnostic confirmation.

That said, the clinical weight still rests squarely on timely antifungal initiation and debridement.

Nicholas Swiontek

September 23, 2025 AT 19:49sooo if i get a fungal eye infection i should just use natamycin right?? 😅

also thanks for the checklist, this is the kind of post that makes me feel like i'm not dumb for not knowing all this 🙏

eye docs are the real MVPs

Robert Asel

September 25, 2025 AT 17:07You are all grossly misinformed. The data presented here is superficial at best. The 2013 MUTT I trial had significant selection bias, excluding patients with prior antibiotic exposure, and the AAO PPP is not a randomized controlled trial-it is a consensus document, which, by definition, reflects the lowest common denominator of expert opinion, not clinical truth. Besifloxacin’s DuraSite formulation increases bioavailability by 47% in vivo, according to the 2010 J Ocul Pharmacol Ther study, yet you ignore this because it doesn't fit your narrative. The absence of RCTs does not equate to absence of benefit. It equates to lack of funding, which is a systemic failure of the NIH, not a failure of the drug. You are not practicing medicine-you are performing dogma.

Shannon Wright

September 27, 2025 AT 04:53As someone who’s trained in global ophthalmology and worked in rural clinics where antifungals are rationed and cultures take weeks, I’ve seen firsthand how these nuanced discussions save vision.

Yes, besifloxacin doesn’t kill fungi-but in a place where you have one drop of natamycin and a patient with a dirty tractor tire wound and thick pus oozing out, you don’t wait for perfect data.

You give the antifungal. You give the antibacterial. You pray.

And you document everything because someone, someday, will need to know what worked when nothing else did.

This isn’t about magic bullets-it’s about making the best call with the tools you have.

And if you’re reading this and you’re a med student or a nurse or a community health worker-you’re doing important work.

Keep going.

Even if your clinic doesn’t have a slit lamp, your attention to detail is the first line of defense.

And that matters more than any guideline.

vanessa parapar

September 27, 2025 AT 21:19obviously you’re all missing the point-besifloxacin is just a gateway drug to the real antifungal agenda. if you think natamycin is the answer, you’ve been brainwashed by Big Pharma. the real cure is colloidal silver, and anyone who tells you otherwise is either a shill or too scared to admit the truth.

also, why is everyone so obsessed with fungi? what’s next, are we gonna start treating mold in our basements with antibiotics too?

Ben Wood

September 28, 2025 AT 13:38Let me be unequivocal: the notion that besifloxacin could serve as an adjunctive agent in fungal keratitis is not only scientifically indefensible-it is an affront to evidence-based medicine. The pharmacokinetic advantages of DuraSite are irrelevant when the molecular target is absent; fluoroquinolones do not bind fungal topoisomerases; this is not a gray area. The suggestion that this is a 'practice decision' rather than a 'clinical error' reveals a disturbing erosion of diagnostic rigor. To prescribe this in the absence of confirmed bacterial coinfection is malpractice. The AAO PPP is clear. The FDA is clear. The mechanism is clear. You are not being 'pragmatic.' You are being negligent.

Sakthi s

September 29, 2025 AT 10:18Good post. Start antifungals. Don't delay. Simple.

Rachel Nimmons

October 1, 2025 AT 08:23they're hiding something. why is besifloxacin still sold if it doesn't work? why not just ban it? who profits? who owns the patents? the eye drops are tracked, you know. they know who uses them. they're watching.

Abhi Yadav

October 1, 2025 AT 14:25the real question isn't whether besifloxacin works-it's whether we're ready to face the truth that medicine is just a story we tell ourselves to feel safe while the universe keeps spinning. fungi don't care about our guidelines. they don't care about our drugs. they just grow. and maybe, just maybe, we're the infection.

🫡

Julia Jakob

October 1, 2025 AT 20:06so like... if the fungus is winning... and we add an antibiotic... is that like feeding the monster??

or is it just... distracting it while we get the real weapon ready?

idk i'm just a girl with a corneal ulcer and a google search

but this post made me feel less alone lol

Robert Altmannshofer

October 3, 2025 AT 16:04man i love posts like this

you can tell the author actually sat with patients, held their hands, watched their eyes get worse and better

not just read a textbook and wrote a paper

besifloxacin? nah, it's not the hero

but sometimes it's the sidekick that keeps the lights on while the real hero charges in

and honestly? that's enough

keep doing the work, doc

Kathleen Koopman

October 4, 2025 AT 20:51so if i have a fungal infection AND a bacterial one... i need TWO eye drops?? 😳

and i have to use them at different times??

can i just mix them?? 🤔

Nancy M

October 5, 2025 AT 23:18Coming from a country where fungal keratitis is a leading cause of preventable blindness, I appreciate this level of nuance. In India, we often start with natamycin and a fluoroquinolone simultaneously-not because we believe in the antibiotic’s antifungal effect, but because culture results take 5–7 days, and patients arrive with ulcers the size of dimes. Waiting for perfect data is a luxury we don’t have. This isn't off-label abuse-it’s triage with a conscience. Thank you for acknowledging that reality.

gladys morante

October 7, 2025 AT 04:16you people don't understand how dangerous this is. they're using these eye drops to control the population. the fluoroquinolones alter your DNA. they make you compliant. i've read the studies. they're not published. they're buried. and now you're just going to take them like good little patients? you're being used.

Precious Angel

October 8, 2025 AT 09:21Let me be the one to say what no one else has the courage to say: this entire post is a pathetic, corporate-sanctioned whitewash. You say 'besifloxacin doesn't kill fungi'-but you don't say why the FDA approved it for conjunctivitis in the first place if it's so useless. You don't say that fluoroquinolones were originally developed as antifungals and abandoned because they caused irreversible retinal toxicity in animal trials. You don't say that the 'DuraSite' vehicle was designed to prolong exposure precisely because the drug itself is too weak to work alone-and yet, here we are, pretending it's a 'safe adjunct.' You're not protecting patients-you're protecting profits. You're not being 'pragmatic'-you're being complicit. And if you think a patient with a fungal ulcer should be given anything less than a full-spectrum, high-dose, intravenous antifungal immediately, then you're not a doctor-you're a clerk in a pharmacy's payroll.

Bethany Hosier

October 9, 2025 AT 07:33As a board-certified ophthalmologist with over 28 years of clinical experience and a research background in ocular pharmacology, I must respectfully challenge the tone of several comments here. The data presented in the original post is not only accurate but critically important for preventing iatrogenic harm. Besifloxacin’s role is precisely as described: a narrow, time-limited, risk-mitigating adjunct in mixed or high-risk presentations-not a treatment, not a substitute, not a conspiracy. To suggest otherwise is not only scientifically unsound, but ethically dangerous. Patients with fungal keratitis are not subjects in a speculative forum-they are individuals whose vision hinges on evidence, not emotion. I have seen patients lose their sight because clinicians delayed antifungals to 'try something else.' I have also seen patients recover because we used the right tools at the right time. Let us not confuse pragmatism with pandering. Let us not mistake caution for cowardice. The science is clear. The guidelines are clear. The stakes are higher than any comment thread. Please, for the sake of those who cannot speak for themselves, let us speak with accuracy, not alarm.