When a pharmacist fills a prescription, they’re not just handing out pills-they’re making decisions that affect patient safety, cost, and trust. The difference between a generic and a brand-name drug isn’t just about price. It’s about how well the pharmacy system can tell them apart, and whether that system is built to do it right. Too often, the confusion between generics and brands leads to errors, delays, or even harm. That’s why generic vs brand identification in pharmacy systems isn’t just a technical detail-it’s a core safety practice.

How Pharmacy Systems Tell Generics Apart from Brands

Pharmacy systems don’t guess. They rely on hard-coded data from federal databases. The foundation is the National Drug Code (NDC), a unique 10- or 11-digit number assigned to every drug product. Every version of a drug-whether it’s the original brand or a generic copy-gets its own NDC. That means two identical pills from different manufacturers have different codes. Systems like Epic, Cerner, and Rx30 use these codes to track inventory, process insurance claims, and prevent duplicates. But NDCs alone aren’t enough. The real magic happens with the FDA’s Orange Book, which lists every approved drug and assigns a Therapeutic Equivalence (TE) code. If a generic has an ‘AB’ code, it means the FDA has confirmed it performs the same way as the brand-name drug in the body. ‘AO’ or ‘AN’ codes mean there’s uncertainty-maybe the drug’s delivery system is different, or it hasn’t been tested thoroughly enough. Systems that ignore TE codes are playing Russian roulette with patient safety. Even trickier are authorized generics. These are brand-name drugs sold under a generic label, made by the same company, with the same ingredients, same factory, same everything. But because they’re labeled as generics, many pharmacy systems flag them as ‘generic’ and assume they can be swapped freely. That’s misleading. A patient on an authorized generic might think they’re switching to a cheaper version, but they’re not switching at all. Systems that don’t distinguish authorized generics from true generics risk confusing patients and providers.Why Branded Generics Make Things Worse

Then there are branded generics-drugs that went through the generic approval process (ANDA) but still carry a brand name. Think of drugs like Errin, Jolivette, or Sprintec. These are chemically identical to their generic equivalents, but they’re marketed like brands. Pharmacy systems often treat them as ‘brand’ drugs because of their names, even though they’re not the original patent-protected version. This creates a mess: a pharmacist might see a prescription for ‘Sprintec’ and think they need to dispense the brand, when the patient’s insurance only covers the generic version. The system doesn’t know they’re the same thing. This confusion is especially common with birth control. A 2022 survey found that 78% of pharmacists reported difficulty distinguishing between branded generics like Tri-Sprintec and their generic equivalents. Why? Because different pharmacy chains use different naming conventions. One chain might list it as ‘Norethindrone/ethinyl estradiol,’ while another calls it ‘Sprintec.’ Without clear mapping to the Orange Book, the system can’t auto-suggest the correct substitution. Patients end up paying more, or worse-getting the wrong pill.Where Systems Fail: Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

Not all drugs are created equal. Some, like warfarin, phenytoin, levothyroxine, and cyclosporine, have a narrow therapeutic index. That means a tiny difference in blood concentration-just 5%-can lead to serious side effects: a stroke, seizures, or organ rejection. For these drugs, bioequivalence matters more than ever. Yet many pharmacy systems still allow automatic substitution. A 2021 report from the Institute for Safe Medication Practices documented 147 adverse events over 18 months linked to inappropriate generic substitution of warfarin. Why? Because the system didn’t flag it. Systems that don’t block substitution for NTI drugs are not just outdated-they’re dangerous. Top-performing systems like Epic’s Beacon Oncology module have built-in rules: if a drug has a TE code of ‘B’ (not therapeutically equivalent) or is listed as NTI, the system blocks substitution and requires prescriber approval. It doesn’t ask. It doesn’t suggest. It just says no. That’s the standard every pharmacy system should meet.

What the Best Systems Do Differently

The best pharmacy systems don’t just identify drugs-they guide decisions. Here’s what they do:- Default to generics: Over 92% of electronic health record systems automatically display generic names first. This isn’t about pushing cost savings-it’s about reducing cognitive load. When the system shows ‘Lisinopril’ instead of ‘Zestril,’ it removes brand bias.

- Flag authorized generics: These systems show a small icon or note saying ‘Authorized Generic’ next to the drug name. Pharmacists know instantly: this is the exact same drug as the brand.

- Integrate with the FDA Orange Book API: The FDA updates its Orange Book monthly. Systems that pull data directly from this API get real-time updates on new generics, TE code changes, and withdrawn products. Systems that rely on static databases are already outdated.

- Use patient-specific alerts: If a patient has had a reaction to a specific generic in the past, the system remembers. It doesn’t just say ‘generic available’-it says ‘generic available, but patient previously reported issues with this manufacturer.’

- Map state laws automatically: In California, pharmacists must document why they didn’t substitute. In Texas, they don’t need to. Systems that don’t auto-adjust based on state rules create compliance risks.

How Patients See It-And Why They Care

Patients don’t care about TE codes or NDCs. They care about whether their pill looks different, whether they’re being charged more, or whether they feel worse after switching. A 2022 Consumer Reports survey found that 89% of patients were satisfied with generic substitution-when they were told why. The problem? 68% of patients didn’t know generics contain the same active ingredients. That’s not a patient education issue-it’s a system issue. The best pharmacy systems don’t just dispense the drug. They print a simple note on the label: ‘This is a generic version of [Brand Name]. Same active ingredient. FDA-approved to work the same way.’ Kaiser Permanente’s system goes further. Their patient portal shows side-by-side comparisons: brand name, generic name, price difference, and a green checkmark saying ‘FDA-approved equivalent.’ As a result, they saw a 37% drop in patients asking to switch back to the brand.

Implementation Challenges-And How to Overcome Them

Adopting best practices isn’t easy. Independent pharmacies often lack the budget to upgrade systems. A 2022 ASHP survey found only 63% of independent pharmacies have full generic identification tools, compared to 97% of hospital systems. Here’s how to fix it:- Start with the Orange Book: Make sure your system pulls data directly from the FDA’s API. Don’t rely on third-party databases that update monthly or quarterly.

- Train staff on TE codes: Pharmacists and technicians need to understand what ‘AB’ means versus ‘BN.’ One hour of training per quarter is enough to prevent costly mistakes.

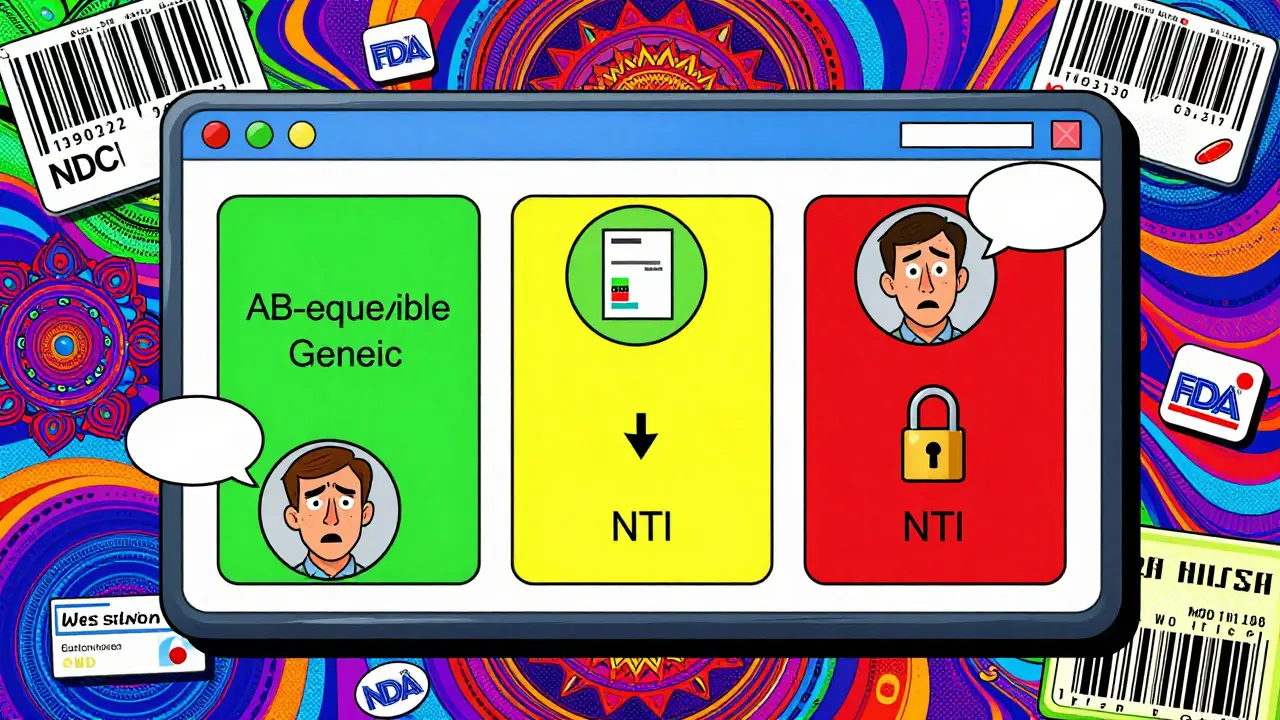

- Use visual cues: Color-code drugs in your system. Green for equivalent, yellow for authorized generic, red for NTI drugs that can’t be substituted.

- Build patient handouts: Use simple graphics: ‘Brand Drug’ vs ‘Generic Drug’ with identical pills and the words ‘Same Active Ingredient.’

- Monitor substitution rates: Track how often generics are overridden. If 30% of prescriptions for lisinopril are still being filled as Zestril, dig into why. Is it the system? The prescriber? The patient?

The Future: AI, Genomics, and Real-Time Alerts

The next wave of pharmacy systems won’t just identify drugs-they’ll predict problems. New AI tools, like those tested in a 2023 JAMIA study, analyze prescription patterns and flag when a patient on levothyroxine suddenly switches from one generic to another. The system doesn’t wait for a reaction-it warns the pharmacist before the refill is filled. The FDA’s 2023 Precision Medicine Initiative is exploring whether genetic markers can determine if a patient responds better to a specific brand. Imagine a system that says: ‘Patient has CYP2C9 variant-avoid generic warfarin. Use brand.’ That’s not science fiction. It’s coming.What You Need to Do Now

If you’re a pharmacist, a pharmacy owner, or a system administrator, here’s your checklist:- Confirm your system pulls live data from the FDA Orange Book API.

- Ensure all NTI drugs are locked from automatic substitution.

- Train staff to recognize authorized generics and branded generics.

- Add patient-friendly explanations to every generic substitution.

- Review your state’s substitution laws monthly-changes happen often.

Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system billions every year. But if your pharmacy system can’t tell them apart from brands-or worse, treats them like they’re different-you’re not saving money. You’re risking lives.

Can a generic drug be as effective as a brand-name drug?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They must also prove bioequivalence-meaning they deliver the same amount of medicine into the bloodstream at the same rate. Studies show generics work just as well for most patients. The only exceptions are narrow therapeutic index drugs, where even tiny differences matter.

Why do some patients feel different after switching to a generic?

Most often, it’s not because the generic is less effective-it’s because the pill looks different. Color, shape, or size can trigger a placebo effect. Some patients also react to inactive ingredients (like dyes or fillers), though this is rare. A 2019 study found 0.8% of patients reported issues after switching antiepileptic drugs. The key is communication: if patients are told ahead of time that the change is safe, their concerns drop significantly.

What’s the difference between an authorized generic and a regular generic?

An authorized generic is made by the same company that produces the brand-name drug, using the same formula and factory. It’s sold under a generic label because the patent expired. A regular generic is made by a different company, often with different manufacturing processes. Authorized generics are chemically identical to the brand; regular generics must meet bioequivalence standards but may differ slightly in how they’re made.

Do pharmacy systems always know which generics are approved?

No. Many systems rely on outdated databases that update only once a month. The FDA releases new generic approvals weekly, and the Orange Book updates monthly. Systems that don’t connect directly to the FDA’s API can be weeks behind. This means a pharmacist might see a drug as ‘not available as generic’ when it’s actually been approved for months.

Can I trust a generic drug if it’s much cheaper than the brand?

Yes. Price doesn’t determine quality. Generics are cheaper because they don’t pay for advertising, clinical trials, or patent protection. The FDA requires them to meet the same manufacturing standards as brands. A $5 generic isn’t a ‘cheap version’-it’s the same drug at a fair price. The only red flag is if a generic is priced so low that it seems suspicious-this could indicate a counterfeit product, which is extremely rare in regulated U.S. pharmacies.

Alex Ogle

February 10, 2026 AT 02:53It's wild how much we take for granted in pharmacy systems. I used to work in a retail chain where the software would swap out levothyroxine like it was aspirin. No warnings. No flags. Just 'generic available.' I once saw a 72-year-old woman come back in tears because she felt 'off' after switching. Turns out, her body reacted to the filler in one brand. We didn't know because the system didn't track manufacturer history. That's not negligence-it's systemic blindness. We need real-time integration with the Orange Book, not quarterly updates. And yes, I'm talking to you, Epic and Cerner. Stop outsourcing patient safety to third-party databases that haven't been updated since 2020.

Brandon Osborne

February 11, 2026 AT 04:36THIS IS WHY AMERICA IS FALLING APART. You people let corporations dictate patient care because 'it's cheaper.' Do you have ANY idea how many people have had strokes because some algorithm decided a $3 generic was 'good enough'? The FDA doesn't test for bioequivalence in real-world conditions. They test in labs with healthy volunteers. Real people have different metabolisms, gut flora, liver function. And yet we treat generics like interchangeable Lego blocks. This isn't healthcare. It's a supply chain optimization exercise. And the patients? They're just cost centers. Wake up. This is murder by spreadsheet.

Marie Fontaine

February 12, 2026 AT 12:10Yessss!! I love this post!! 🙌 Seriously, the part about authorized generics? Mind blown. I had no idea they were literally the same pill, just labeled differently. My pharmacist just told me 'it's generic' and I thought I was getting the cheap version. Turns out I was getting the exact same thing my mom takes. Sooo much less scary now. Also, the Kaiser patient portal thing? That's genius. Why doesn't everyone do this?? 🤯

Ken Cooper

February 13, 2026 AT 02:21ok so i just read this whole thing and i need to say-this is the most important thing i’ve ever read about pharmacy. i work in a small clinic and we use a system that still has like 500 drugs flagged as 'no generic available' when they’ve been generic for 3 years. we had a guy on warfarin get switched accidentally and his inr went to 8. he almost bled out. no one knew because the system didn’t flag it. i’ve been begging our admin to upgrade but they say 'it’s not broken.' bro it’s broken. it’s literally killing people. pls someone tell me how to get this to my rep at our ehr vendor. i’m ready to start a petition.

MANI V

February 14, 2026 AT 23:45How can you trust a system built by American corporations that prioritize profit over people? The FDA is a puppet of Big Pharma. They approve generics with zero long-term studies. The real reason they push generics is to eliminate competition. You think the 'same active ingredient' matters? What about excipients? The dyes? The binders? Those are often toxic. And the manufacturers? They're in China. Do you really believe your pills aren't contaminated? This isn't healthcare. It's chemical warfare disguised as cost-saving.

Random Guy

February 15, 2026 AT 02:00So let me get this straight… we’re paying billions to make sure a pill looks different so we can feel better about it? Like… we’re basically paying for placebo branding? I’m just here for the drama.

Ryan Vargas

February 16, 2026 AT 09:22The entire pharmaceutical industrial complex is a monument to epistemological fraud. The FDA’s Orange Book is not a scientific document-it is a bureaucratic artifact constructed to satisfy regulatory formalism while obscuring the ontological instability of bioequivalence. The notion that 'same active ingredient' implies 'same therapeutic outcome' is a semantic sleight of hand. Bioequivalence is measured under controlled, artificial conditions that bear no relation to the human body in situ. The system’s reliance on NDCs and TE codes is not a solution-it is a performative ritual of compliance, designed to absolve institutions of moral responsibility while continuing to commodify biological vulnerability. We are not managing drug substitution. We are managing the illusion of safety.

Tasha Lake

February 17, 2026 AT 09:32As a clinical pharmacist, I’ll add: the biggest blind spot is branded generics. We had a patient on Sprintec who got switched to a 'generic' that turned out to be a branded generic-same pill, different label, same price. Insurance didn’t cover it because it was 'brand,' but the system didn’t flag it. We had to manually override. This is why we need direct Orange Book API integration-no middleman, no lag. Also, state laws vary so wildly that automated rules are mandatory. California requires documentation; Texas doesn’t. Systems that don’t auto-adjust are legal time bombs.

Sam Dickison

February 19, 2026 AT 03:38100% agree. I work in a hospital and our system blocks substitution for NTI drugs by default. It’s a lifesaver. Also, we color-code: green = AB, yellow = authorized generic, red = NTI. Techs love it. No more guessing. And we print that simple note on the label: 'Same active ingredient. FDA-approved.' Patients stop asking questions. It’s that easy. Why isn’t this standard everywhere? Budgets? Training? Nah. It’s inertia. And inertia kills.

John McDonald

February 20, 2026 AT 22:33Just wanted to say thanks for laying this out so clearly. I’ve been pushing for this at my pharmacy for years. We finally got our system updated last month-live Orange Book feed, color coding, patient notes. Our error rate dropped 60%. Not because we’re geniuses. Because the tools were there. We just needed someone to say: 'Do this.' So thank you. And if you’re reading this and work at a pharmacy: don’t wait for someone else to fix it. Start with the Orange Book API. It’s free. It’s real. And it’s the bare minimum we owe our patients.

Andy Cortez

February 22, 2026 AT 05:45Generic drugs? More like generic *thinking*. They're not the same. They're not even close. I’ve been on the same med for 12 years. Switched to generic. Felt like I got hit by a truck. Turned out the manufacturer used a different coating that dissolved too fast. My doc said 'it’s bioequivalent.' Yeah, in a lab. Not in my stomach. The system doesn’t care. It just says 'approved.' Meanwhile, I’m sweating bullets every time I refill. This isn’t progress. It’s a scam.

Alex Ogle

February 22, 2026 AT 15:06Actually, the system I work with now has patient-specific alerts. Last week, a guy came in for his lisinopril refill. The system popped up: 'Patient previously reported dizziness with Mylan brand. Consider switching to Teva.' He didn’t even ask. Just nodded. That’s the future. Not just knowing the drug. Knowing the person.