When someone says they take medication for anxiety or depression, the reaction isn’t always understanding. Sometimes it’s silence. Sometimes it’s a raised eyebrow. Sometimes it’s a comment like, "Are you sure you need that?" or "I don’t trust pills for the mind." These reactions aren’t just awkward-they’re harmful. They keep people from getting the care they need. And the truth is, mental health medication stigma is one of the biggest reasons people stop taking their meds-or never start.

Why Mental Health Medications Are Treated Differently

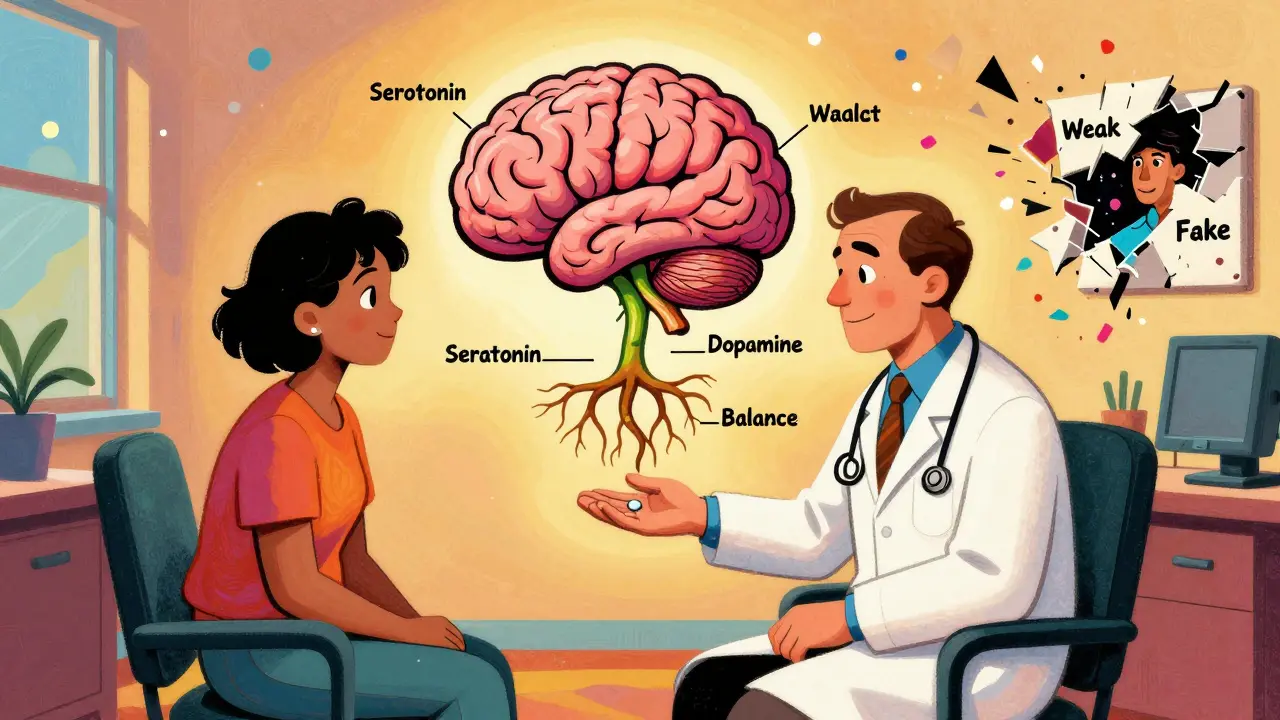

Think about how people talk about insulin for diabetes. Or blood pressure pills. No one questions whether those are "real" medicine. But ask someone if they take antidepressants, and suddenly, it’s a conversation about weakness, addiction, or "chemical imbalance" as if it’s not a biological condition. The difference isn’t medical-it’s cultural. Studies show 75% of people don’t see mental health conditions requiring medication as chronic illnesses, like heart disease or asthma. That’s not ignorance-it’s stigma. And it’s built on myths. Many believe psychiatric meds are "mind-altering" or "just for people who can’t handle life." But the data doesn’t back that up. Antidepressants work for 40-60% of people with moderate to severe depression-similar to how statins work for cholesterol. They don’t change your personality. They help your brain function the way it should. Even worse, 25% of people prescribed antidepressants quit within 30 days-not because the meds don’t work, but because they feel ashamed. One patient told me she hid her pill bottle under her toothbrush because she didn’t want her roommate to see it. Another said he stopped taking his meds after his boss joked, "So, are you on the happy pills now?"How Language Fuels the Stigma

Words matter. A lot. The National Institute of Mental Health found that using terms like "meds," "pills," or "drugs" increases negative attitudes by 41%. But when providers say "medication," "treatment," or "brain chemistry support," people respond differently. It’s not just semantics-it’s framing. In clinical settings, replacing "You’re on antidepressants" with "You’re taking medication to help balance your brain chemicals" reduces patient shame by 27%, according to the American Psychiatric Association. It’s not about being politically correct. It’s about accuracy. Insulin regulates blood sugar. SSRIs regulate serotonin. Both are biological interventions. Even small shifts in language help. Instead of saying, "I’m on medication," try, "I take medication for my mental health, just like someone else takes it for their thyroid." That normalizes it. It connects mental health to other health conditions people already accept.What Works: Evidence-Based Strategies

There’s no single fix for stigma, but research shows some approaches consistently reduce it. Normalize it. The Mayo Clinic recommends a simple three-step approach:- Normalize: "Many people take medication for mental health conditions-just like others take pills for high blood pressure."

- Educate: "This medication helps your brain chemistry return to balance. It’s not a cure-all, but it makes therapy more effective."

- Personalize: "For me, it’s the difference between being able to get out of bed and feeling stuck all day."

What Doesn’t Work-and Why

Not every "awareness" effort helps. Some well-intentioned campaigns backfire. For example, "hallucination simulations" meant to build empathy among medical students sometimes increased stigma by 15%. Why? Because they focused on extreme symptoms instead of everyday recovery. People walked away thinking, "That’s not me," not "That’s someone who needs help." Another problem? Telehealth. With more therapy and prescribing happening online, 41% of patients say they feel less comfortable discussing meds over video. They’re not in the same room as their provider. They’re on their couch, maybe with their kids nearby. No privacy. No safety. That’s a new kind of stigma barrier. And then there’s the workplace. A 2022 Mental Health America survey found 43% of people who disclosed their medication use faced some kind of discrimination-18% were passed over for promotions. That’s real. That’s scary. And it’s why many stay silent.How to Talk About It-Without Apologizing

You don’t owe anyone an explanation. But if you want to, here’s how to do it without inviting judgment:- "I take medication for my mental health. It’s part of my treatment plan, like physical therapy or a doctor’s visit."

- "I used to think I should handle it on my own. Turns out, my brain needed support-just like my knee did after surgery."

- "It’s not about being weak. It’s about being smart enough to use all the tools available."

- "I don’t talk about it because I’m embarrassed. I talk about it because I want others to know they’re not alone."

What’s Changing-and What’s Next

There’s progress. The CDC’s "Medications as Medicine" campaign is reframing psychiatric drugs as part of chronic disease care-like insulin or statins. Early results show a 21% increase in positive attitudes in pilot areas. By 2026, the American Medical Association predicts 65% of antidepressant prescriptions will come from primary care doctors-not psychiatrists. That’s huge. When your regular doctor prescribes your meds, it stops feeling like a "mental health thing." It becomes part of your overall health. New tools are helping too. The SAMHSA "Medication Conversation Starter" app has been downloaded over 150,000 times. It gives you ready-made responses for common stigmatizing comments: "I get that you’re worried, but this isn’t the same as recreational drugs. It’s regulated, tested, and prescribed." And it’s not just patients changing. Medical students who watch short videos of their future colleagues talking about their own appropriate medication use show a 37% drop in stigma. Role models matter.You’re Not Alone

If you’re taking medication and feel ashamed-know this: you’re not broken. You’re not weak. You’re someone who’s doing what’s necessary to feel better. And you’re part of a growing group of people who are choosing honesty over silence. The stigma won’t disappear overnight. But every time you speak up, every time you use the word "medication" instead of "pills," every time you normalize it in your own life-you chip away at it. And that’s how change happens.Why do people feel ashamed about taking mental health medication?

People feel ashamed because of deep-rooted myths-that psychiatric meds are "not real medicine," that they change your personality, or that needing them means you’re weak. These beliefs are fueled by media portrayals, cultural stigma, and even well-meaning but misinformed comments from friends or family. Many also fear judgment at work or in social settings, especially since 43% of people who disclose medication use report some form of discrimination.

Is it true that mental health meds are addictive?

Most psychiatric medications are not addictive. Antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics don’t create the euphoria or cravings associated with addictive substances. Some medications, like benzodiazepines, can cause dependence if misused long-term, but they’re prescribed cautiously and monitored closely. The real issue is withdrawal symptoms when stopping abruptly-which is why tapering under medical supervision is essential. This is not addiction; it’s physiological adjustment.

How can I talk to my doctor about my concerns with medication?

Start by being honest. Say something like, "I’m open to medication, but I have some worries about side effects or stigma." A good provider will listen without judgment. Ask questions: "How does this work?", "What are the success rates?", "Are there alternatives?" The "Two-Question Approach"-"How do you feel about taking medication?" and "What concerns do you have?"-helps providers tailor their support. You’re not being difficult; you’re being an active partner in your care.

What should I do if someone makes a stigmatizing comment about my meds?

You don’t have to respond, but if you want to, keep it calm and factual. Try: "I know it’s not something everyone understands, but this medication helps me manage my condition, just like insulin helps someone with diabetes." If the person is dismissive, you can say, "I appreciate your concern, but this is part of my health plan." You’re not obligated to defend yourself. Your health comes first.

Can medication stigma affect how well the treatment works?

Yes. Shame can lead to skipping doses, hiding pills, or stopping treatment entirely. A 2022 study found 37% of patients stopped taking their meds because of shame. When people feel judged, their motivation drops. But when they feel supported-by their provider, their family, or their community-they’re more likely to stick with treatment. Reducing stigma isn’t just about dignity; it’s about effectiveness.

Are there cultures where mental health medication stigma is stronger?

Yes. In some Asian American communities, for example, cultural beliefs about mental illness being a family shame or a personal failing lead to 47% lower antidepressant adherence compared to White Americans. In other cultures, spiritual or holistic views of health may lead to skepticism about pharmaceuticals. Understanding these differences helps providers tailor conversations and avoid assumptions.

How can I support someone who’s taking mental health medication?

Listen without judgment. Don’t ask, "Do you really need that?" Instead, say, "I’m glad you’re taking care of yourself." Avoid comparing their experience to others. Don’t push them to quit or "try natural remedies" unless they ask. Offer practical support-like reminding them to refill prescriptions or accompanying them to appointments. Your acceptance can be the difference between sticking with treatment and giving up.

If you’re a provider, your words carry weight. If you’re a patient, your courage matters. And if you’re someone who’s never thought about this before-now you know. Mental health medication isn’t a last resort. It’s a tool. And like any tool, it works best when it’s not hidden.

Jon Paramore

December 20, 2025 AT 16:36SSRIs modulate serotonin reuptake via SERT inhibition-similar to how beta-blockers affect adrenergic receptors in hypertension. The pharmacodynamics are well-characterized. The stigma isn’t biological; it’s sociocultural. We don’t shame diabetics for insulin, so why shame someone for fluoxetine? It’s a neurochemical intervention, not a moral failing.

Swapneel Mehta

December 20, 2025 AT 21:58It’s strange how we accept pills for the body but not the mind. If your liver needs help, you take medicine. If your brain needs help, you’re weak? That doesn’t add up. I’ve seen people recover after starting treatment-really recover. It’s not magic. It’s medicine.

Peggy Adams

December 22, 2025 AT 21:07lol so now we’re calling antidepressants ‘brain chemistry support’? next they’ll say caffeine is ‘neurological performance enhancement’. they’re just drugs. they alter your state. stop pretending it’s science.

Sarah Williams

December 24, 2025 AT 19:54Exactly. People need to stop treating mental health like it’s a separate category. It’s biology. Your brain is an organ. If you have a tumor on your pancreas, you get surgery. If you have a serotonin imbalance, you get medication. Same thing. Stop the drama.

Theo Newbold

December 26, 2025 AT 19:3575% of people don’t see it as chronic illness? That’s because most of them aren’t idiots. You can’t quantify ‘chemical imbalance’ like you can glucose levels. This whole narrative is corporate propaganda pushed by Big Pharma to sell more pills. They’ve been doing this since the 90s.

Jay lawch

December 27, 2025 AT 18:33Listen, in India we have Ayurveda, yoga, pranayama-centuries of holistic healing. And now you Westerners come with your chemical cocktails and call it ‘science’? You don’t understand the soul. You don’t understand the mind. You just want to numb it. This is colonization of consciousness. Your pills are not medicine-they are control mechanisms disguised as care.

Christina Weber

December 29, 2025 AT 12:09There’s a grammatical error in your third paragraph: ‘Think about how people talk about insulin for diabetes. Or blood pressure pills.’ That’s a sentence fragment. Also, ‘chemical imbalance’ is an outdated and inaccurate term-neuroscientists haven’t validated it as a diagnostic criterion since the early 2000s. You’re perpetuating misinformation under the guise of education.

Dan Adkins

December 31, 2025 AT 02:11While I acknowledge the statistical evidence presented regarding the efficacy of pharmacological interventions in the management of mood disorders, I must respectfully posit that the cultural framing of such interventions as equivalent to cardiovascular therapeutics may inadvertently undermine the existential dimensions of human suffering. The reduction of psychological distress to biochemical parameters risks obfuscating the phenomenological experience of the individual.

Erika Putri Aldana

January 1, 2026 AT 09:03yeah but like… what if you just need to go outside more? or stop scrolling tiktok? i took a walk yesterday and my anxiety went down. why do we need chemicals for everything? it’s lazy. you’re just avoiding the real work.

Adrian Thompson

January 2, 2026 AT 16:26Oh wow, so now we’re comparing antidepressants to insulin? Next you’ll say the CIA invented SSRIs to pacify the masses. And don’t get me started on the ‘medication conversation starter’ app. That’s not empowerment-that’s behavioral conditioning. You’re training people to accept chemical compliance like good little drones.

Teya Derksen Friesen

January 3, 2026 AT 14:41This is one of the most thoughtful, evidence-based pieces I’ve read on this topic in years. The framing of mental health medication as a tool-not a weakness-is exactly what’s missing from public discourse. Thank you for writing this. It’s not just informative-it’s necessary.

Sandy Crux

January 5, 2026 AT 01:39...And yet, despite all this data, the underlying assumption remains unchallenged: that mental distress is a pathology requiring pharmacological correction... when perhaps, just perhaps, it is a rational response to an irrational world? You treat the symptom, not the system. That’s not healing-that’s appeasement.

Hannah Taylor

January 6, 2026 AT 06:13so like… if you’re on meds for anxiety… does that mean you’re not really ‘fixed’? like… what if you just need to be stronger? i mean… my cousin took them for a year and then quit and now she’s fine. so… why do people need them forever? just saying.