Diabetic nephropathy isn't just a complication of diabetes-it's the leading cause of kidney failure worldwide. If you have diabetes and your kidneys are leaking protein, you're not just dealing with high blood sugar anymore. You're facing a silent, progressive disease that can lead to dialysis or transplant. But here’s the good news: two types of blood pressure medicines-ACE inhibitors and ARBs-have been proven to slow this damage, and controlling protein in your urine is key to making them work.

What Is Diabetic Nephropathy?

Diabetic nephropathy starts when high blood sugar damages the tiny filters in your kidneys, called glomeruli. These filters normally keep protein in your blood, but when they’re damaged, protein leaks into your urine. This is called albuminuria. Doctors diagnose it when you have two urine tests over three months showing more than 30 mg of albumin per gram of creatinine. It’s not just about urine tests, though. Many people also show a drop in kidney function, measured by eGFR below 60 mL/min/1.73 m². Left unchecked, this leads to kidney failure.

What makes this especially dangerous is that it often has no symptoms until it’s advanced. No swelling, no pain, no warning. That’s why regular screening is critical for anyone with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Catching it early means you can still stop it.

Why ACE Inhibitors and ARBs Are First-Line Treatment

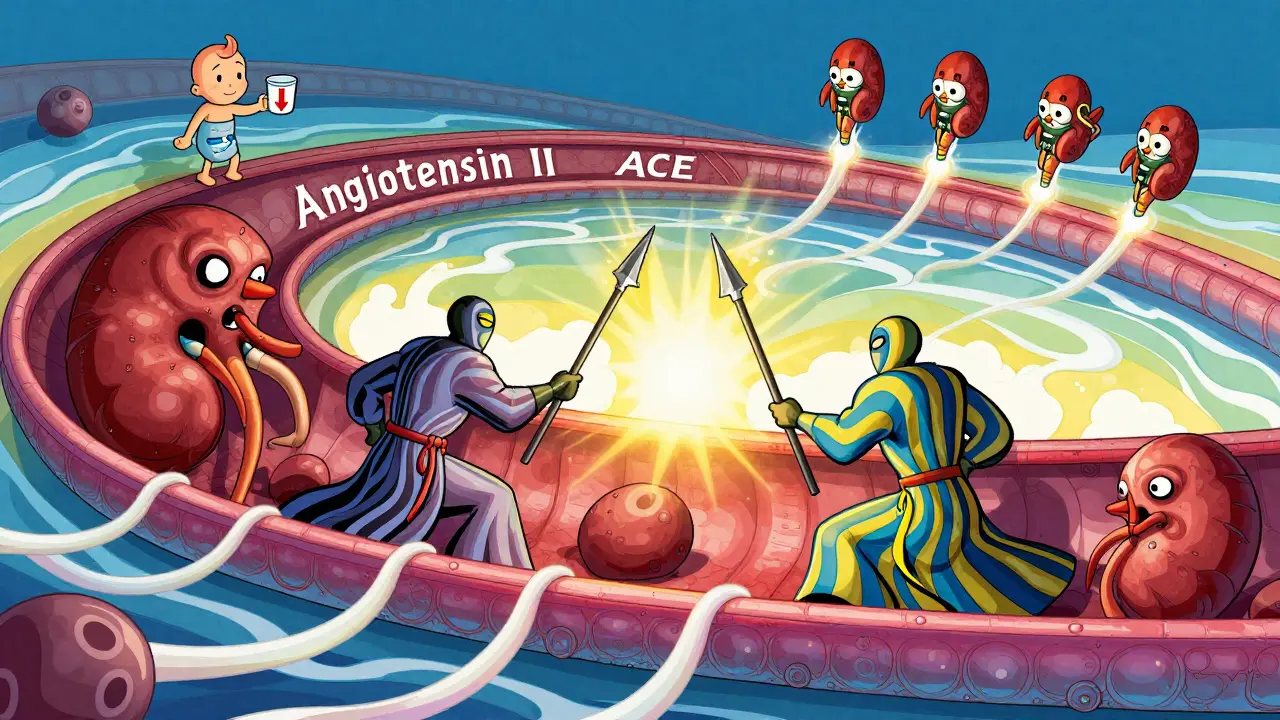

For over 20 years, ACE inhibitors and ARBs have been the go-to treatment for diabetic nephropathy-not because they lower blood pressure alone, but because they do something unique: they reduce protein leakage from the kidneys. This isn’t just a side effect. It’s the main reason they work.

Both drugs block the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), a hormone pathway that tightens blood vessels and increases pressure inside the kidney’s filtering units. High pressure crushes the delicate filters, causing more protein to escape. ACE inhibitors stop the body from making angiotensin II. ARBs block angiotensin II from binding to receptors. Either way, pressure drops inside the kidneys, protein leaks slow down, and kidney damage slows.

Studies like the RENAAL and IDNT trials showed ARBs like losartan and irbesartan cut the risk of kidney failure by up to 30% in people with severe albuminuria. ACE inhibitors like captopril, ramipril, and benazepril showed similar results. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) 2025 guidelines say these drugs aren’t just an option-they’re the standard for anyone with diabetes, high blood pressure, and kidney damage.

Protein Control Is the Goal, Not Just Blood Pressure

Many doctors and patients think the goal is just to get blood pressure under 130/80. That’s important, but it’s not enough. The real marker of success is how much protein you’re losing in your urine. If your albuminuria doesn’t drop after starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB, the treatment isn’t working as it should.

Research shows that the more protein you reduce, the slower your kidney function declines. A 50% drop in urine protein within the first six months is linked to much better long-term outcomes. That’s why doctors don’t just prescribe these drugs-they monitor your urine closely, often every 3 to 6 months after starting treatment.

Don’t be fooled if your blood pressure drops but your protein stays high. You may need a higher dose. Many patients are started on low doses out of fear of side effects, but clinical trials used much higher doses-and that’s what delivered results. The ADA says: if you can tolerate it, use the maximum approved dose.

Dosing Matters-And Most People Are Underdosed

Here’s a harsh truth: most people with diabetic nephropathy aren’t getting the dose they need. Studies show only 60-70% of eligible patients are even prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB. Of those, many are on doses too low to protect their kidneys.

Take captopril: the dose used in trials for diabetic nephropathy was 25 mg three times daily. Many doctors start at 12.5 mg once a day. That’s not enough. Benazepril? Trials used 20-40 mg daily. Ramipril? Up to 20 mg a day. But in real-world clinics, doses are often half that.

Why? Fear of side effects. One common concern is rising creatinine. If your creatinine goes up by less than 30% after starting the drug, don’t stop it. That’s not kidney damage-it’s the drug doing its job. Lowering pressure inside the kidney can temporarily reduce filtration, making creatinine rise. But that’s a sign the drug is working, not failing. Stopping it because of this is one of the biggest mistakes in diabetes care.

Don’t Combine ACE Inhibitors and ARBs

You might think doubling up would help. After all, two drugs are better than one, right? Not here. Three major trials-VA NEPHRON-D, ONTARGET, and ALTITUDE-showed combining an ACE inhibitor with an ARB doesn’t slow kidney disease any further. Instead, it triples your risk of dangerously high potassium levels (hyperkalemia) and doubles your risk of sudden kidney injury.

Same goes for adding a direct renin inhibitor like aliskiren. No extra benefit. Just more danger. The American Diabetes Association and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) both say: pick one. ACE inhibitor or ARB. Not both.

Other Medications and What to Avoid

ACE inhibitors and ARBs are the foundation, but sometimes you need more to control blood pressure. That’s where diuretics, calcium channel blockers, and beta blockers come in. These are used as add-ons-not replacements.

But here’s a dangerous combo to avoid: ACE inhibitors or ARBs with NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen. These painkillers reduce blood flow to the kidneys. When you mix them with RAAS blockers, your kidneys can shut down suddenly, especially if you’re dehydrated or on a diuretic like furosemide.

Even common diuretics can be risky. Loop diuretics like Lasix or Demadex are sometimes needed for swelling or heart failure, but they increase the chance of kidney injury when paired with ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Always tell your doctor what painkillers or supplements you’re taking.

What About Newer Drugs Like SGLT2 Inhibitors?

Yes, newer drugs like empagliflozin and dapagliflozin (SGLT2 inhibitors) have shown impressive kidney protection. But here’s the key point: every major trial that proved their benefit did so in patients who were already taking an ACE inhibitor or ARB at maximum tolerated doses.

That means SGLT2 inhibitors aren’t replacements-they’re teammates. If you can’t take an ACE inhibitor or ARB because of side effects like cough or swelling, then yes, an SGLT2 inhibitor might be your first choice. But if you can tolerate one of the RAAS blockers, start there first. Then add the SGLT2 inhibitor on top.

Same goes for nonsteroidal MRAs like finerenone. These are powerful, but only after RAAS blockers are optimized.

Who Shouldn’t Take These Drugs?

Not everyone needs them. The NIH and ADA are clear: if you have diabetes but no high blood pressure and no protein in your urine, don’t start an ACE inhibitor or ARB just to “prevent” kidney disease. Studies show no benefit in people with normal kidney function and normal urine protein levels.

Also, avoid these drugs if you’re pregnant, have a history of angioedema (severe swelling from ACE inhibitors), or have severely narrowed arteries to your kidneys. And never start them if your potassium is already high.

What’s the Bottom Line?

Diabetic nephropathy is serious, but it’s not inevitable. If you have diabetes and kidney damage, ACE inhibitors and ARBs are your best tools. But they only work if you take them at the right dose, for the right reason, and without dangerous combinations.

Here’s what you need to do:

- Get your urine tested for albumin at least once a year if you have diabetes.

- If protein is high or your kidney function is low, ask your doctor about starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB.

- Don’t settle for low doses. Push for the highest tolerated dose.

- Don’t stop the drug if your creatinine rises less than 30%-that’s normal.

- Avoid NSAIDs and never combine ACE inhibitors with ARBs.

- Ask about adding an SGLT2 inhibitor if your doctor hasn’t mentioned it.

The goal isn’t just to live longer. It’s to avoid dialysis. To keep your kidneys working. To stay off the transplant list. ACE inhibitors and ARBs don’t cure diabetic nephropathy. But when used right, they give you the best shot at keeping your kidneys alive for years to come.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can ACE inhibitors or ARBs reverse kidney damage in diabetic nephropathy?

They don’t reverse existing damage, but they can stop or significantly slow further decline. Studies show that reducing proteinuria by 50% or more can delay progression to kidney failure by years. The goal is preservation, not reversal.

Why is captopril the only ACE inhibitor FDA-approved for diabetic nephropathy?

Captopril was the first ACE inhibitor tested in large trials specifically for diabetic kidney disease and showed clear benefit. Other ACE inhibitors like ramipril and benazepril have similar effects, but they weren’t tested in the same way for this exact use. So while captopril has the official label, other ACE inhibitors are widely used and considered equally effective based on clinical evidence.

What if I get a dry cough from an ACE inhibitor?

A persistent dry cough is a common side effect of ACE inhibitors, affecting up to 20% of users. If it’s bothersome, your doctor can switch you to an ARB, which doesn’t cause this side effect. ARBs work just as well for kidney protection and are often preferred for this reason.

How often should I get my kidney function checked?

When you start an ACE inhibitor or ARB, check your serum creatinine and potassium within 1-2 weeks, then again at 4-6 weeks. After that, every 3-6 months if stable. If your kidney function changes or you’re on other medications, your doctor may check more often.

Can I stop taking these drugs if my blood sugar improves?

No. Even if your blood sugar is now well-controlled, the kidney damage from past high sugars can still progress. ACE inhibitors and ARBs protect your kidneys regardless of current glucose levels. Stopping them increases your risk of kidney failure, even with good diabetes control.

dean du plessis

December 28, 2025 AT 12:55Been living with type 2 for 18 years and my doc never mentioned albuminuria until my eGFR dropped to 58. Glad I found this. No symptoms. Just felt tired. Now I’m on ramipril 10mg daily and getting urine tests every 3 months. No cough. No drama. Just keeping my kidneys alive.

Caitlin Foster

December 29, 2025 AT 05:44So let me get this straight… you’re telling me I’ve been taking ibuprofen for my back pain for 5 years and I’ve been slowly killing my kidneys?? 😳 I’m switching to acetaminophen TODAY. Also, why does everyone act like ACE inhibitors are magic? They gave me a cough so bad I cried during Zoom meetings. ARBs are my new BFF. 🙌

Anna Weitz

December 30, 2025 AT 01:27ACE inhibitors work because they lower pressure in the glomeruli but nobody talks about how the pharmaceutical industry pushed these drugs hard after the 1990s trials and suppressed alternatives. The real solution is diet and fasting. Your kidneys heal when you stop flooding them with glucose and sodium. These pills are just a bandaid on a bullet wound

John Barron

December 30, 2025 AT 05:13As a nephrologist with 22 years in practice, I must emphasize: the RENAAL and IDNT trials remain the gold standard. ARBs reduce proteinuria by 30–40% in responders. However, the critical metric is not BP-it’s the albumin-to-creatinine ratio. If your ACR doesn’t decrease by 30% within six months, you’re not optimized. Also, never combine with NSAIDs. I’ve seen acute renal failure in 72 hours from one Advil after starting an ARB. It’s not theoretical. It’s clinical fact.

Kylie Robson

December 31, 2025 AT 18:58From a pharmacokinetic standpoint, the RAAS blockade effect is dose-dependent and saturable. Suboptimal dosing leads to incomplete angiotensin II suppression, resulting in escape phenomena via alternative pathways like chymase. Hence, the ADA’s recommendation for maximum tolerated dosing is not arbitrary-it’s mechanistically grounded. Furthermore, the transient rise in serum creatinine reflects afferent arteriolar vasodilation, not tubular necrosis. This is a hemodynamic shift, not structural injury. Misinterpretation leads to premature discontinuation and accelerated progression.

Miriam Piro

January 1, 2026 AT 22:14Who really funds these ‘trials’? Big Pharma. They’ve been pushing ACE inhibitors since the 80s. The real reason they don’t want you to combine ARBs and ACEIs? Because then you’d need two prescriptions and they’d lose monopoly control. And don’t get me started on SGLT2 inhibitors-those are just sugar excreters that make you pee more and cost $800 a month. Meanwhile, your kidneys are just trying to heal. Why not try a keto diet? Or intermittent fasting? Or drinking lemon water? No one talks about that. The system doesn’t profit from lifestyle. Only pills.

Kishor Raibole

January 2, 2026 AT 01:19It is imperative to underscore the clinical significance of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the pathophysiology of diabetic glomerulosclerosis. The administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, as elucidated in landmark randomized controlled trials, confers renoprotective benefits independent of blood pressure reduction. It is further incumbent upon the treating physician to ensure that the prescribed dosage aligns with the therapeutic thresholds established in the RENAAL and IDNT protocols. Subtherapeutic dosing constitutes a deviation from evidence-based standards and may precipitate accelerated renal decline. Furthermore, the concomitant use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents is contraindicated due to the risk of acute interstitial nephritis and prerenal azotemia. One must exercise due diligence in patient counseling and pharmacological optimization.

Jane Lucas

January 2, 2026 AT 19:43i had a dry cough for 3 months on lisinopril… switched to losartan and boom. no more cough. also my doc never told me to check my urine protein. i found out by accident. now i do it every 4 months. my numbers are down. thanks for this. 💙

Todd Scott

January 4, 2026 AT 00:08As someone who grew up in South Africa with limited access to specialists, I learned the hard way: if you’re diabetic and your doctor doesn’t mention urine tests or ACE inhibitors, ask. Loudly. I had to travel 300km to get my first ACR test. Found out I had microalbuminuria. Started on benazepril 10mg. Got it up to 40mg over 6 months. My creatinine went up 25%-scared me at first. But my nephrologist said, ‘That’s the drug working.’ Two years later, my kidney function is stable. No dialysis. No transplant. Just smart choices and persistence. Don’t wait until you’re swollen and tired. Test early. Dose right.

Liz MENDOZA

January 5, 2026 AT 03:32To anyone reading this and feeling overwhelmed: you’re not alone. I was diagnosed with diabetic nephropathy last year. I cried. I felt guilty. But this post? It gave me a roadmap. I’m on losartan 150mg now. My ACR dropped from 320 to 89 in 8 months. My doctor checks my potassium every 3 months. I avoid NSAIDs like the plague. I even joined a support group. It’s not easy, but it’s manageable. You’re not just a patient-you’re someone who’s fighting. And you’re doing better than you think.

Elizabeth Alvarez

January 5, 2026 AT 17:04They say ACE inhibitors protect your kidneys… but what if the real problem is the glyphosate in our food and water? What if the diabetes epidemic is caused by GMO corn syrup and the government knows it? The FDA approved these drugs because they’re profitable, not because they fix the root cause. And why do they never mention that diuretics like Lasix are used to mask kidney failure symptoms? The whole system is rigged. You think your doctor is helping you? They’re just following the protocol. The real cure? Clean water. Organic food. And a complete detox. But you won’t hear that from Big Pharma. They want you dependent. Forever.